The Absurdity of Madrid Central

19/06/2019

Tiempo de lectura: 3 minutos

According to the highly regarded opinion of Carlos Herrera, traffic restriction in Central Madrid is an absurdity. Not only Herrera thinks this way: there is a powerful force of public opinion that wants to diminish the restriction of traffic in the most historically important areas in the capital of Spain. Everyone is entitled to an opinion, but there are a few hard facts that say otherwise: controlling traffic in Central Madrid is a very serious matter.

Same as the collection of garbage or sewage, the dissolving of traffic is a necessity for a city that wants to function well. Just as we do not want to go back to having yards full of garbage or to the cry of «Agua va!», we also do not want a city where 80% of the space is occupied by smoking and noisy cars.

The aforementioned evaporation of traffic does not depend on the will of the municipal councilors, it is an obligatory measure that is put in place when there is no other choice. For example, in 1969, in the midst of Franco’s dictatorship, the elimination of traffic in Calle de Preciados in Madrid took place. According to the anti-Madrid Central criterion it was a clearly anti-systemic measure and denial of freedom. The halt to traffic in Calle de Preciados occured because the street was unable to function due to the the clash of intense vehicle traffic with rising pedestrian traffic.

This was done after the traffic became a problem, out of sheer necessity and to avoid greater evils, in many streets and squares currently pedestrianized in Madrid (Callao, Arenal, Carretas, Fuencarral, the list goes on). All of them have multiplied their commercial and urban value in general and are crowded with people around the clock.

The next step is to restrict traffic in other areas of the city, such as done in the superblocks (superilles) of Barcelona. An urban toll (Congestion Charge) can also be established as was done in London. The solution in Madrid was the Residential Priority Areas (APRs) in which only residents could circulate in cars, but the four APRs consequently occupy almost the entirety of the Centro district. The only thing Central Madrid has done is unite the four APRs into one, which coincides with the district.

There are many steps that can be taken to improve the city, reduce the space occupied by cars, noise (caused by traffic by 80%), accidents (killing 50 people in Madrid each year 30 years ago, just over 10 people now) and air pollution as well. The normal thing in a large European capital, such as Berlin, London or Copenhagen, is to create a large area of traffic restriction in the center of the city. Compared to those restriction areas, Central Madrid is really quite modest.

Cities are hard nuts to crack, presenting many real and stubborn obstacles to the imagination and the will of their rulers. Within a decade, the model of Central Madrid will have extended to all of the Almendra Central (the area of Madrid that located within the confines of the M-30 ring road, traditionally comprised of the seven districts of Centro, Arganzuela, Retiro, Salamanca, Chamartín, Tetuán, and Chamberí). This will not be for any political wager, but out of pure necessity, just as the drainage route and the organized collection of garbage was. Of course, we must solve the problem of professionals who must enter the restricted area for their commute to work. Currently it is not clear if they will be fined or not, and the procedure to obtain permission to travel through Central Madrid seems somewhat cumbersome. Madrid Central and its successor must be accessible for everyone, except for those who insist on visiting the center with their car.

Jesús Alonso Millán

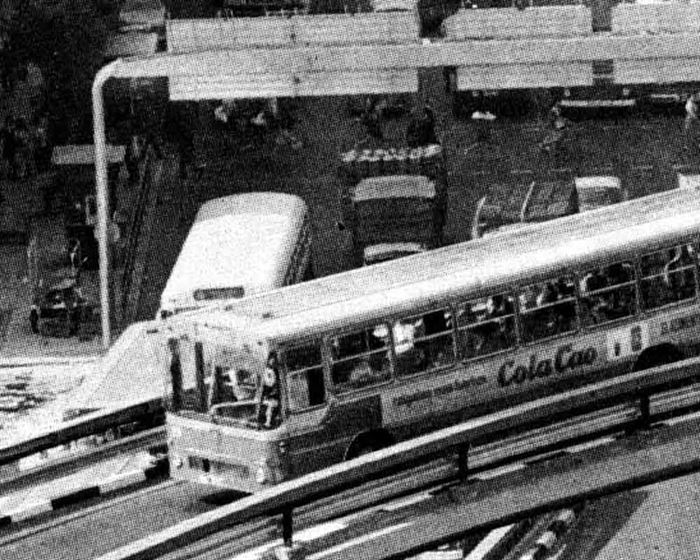

Photography: The overpass of Atocha, in 1969. Will this type of solutions return for traffic jams?